Petrópolis

Petrópolis, 1962

Petrópolis, a small town in the forested hills of the Serra dos Órgãos, in the valley of the Quitandinha and Piabanha rivers, is a popular Brazilian holiday resort. Its history dates to the early 19th century, when Emperor Pedro I built his summer palace there, and when his son, Emperor Pedro II, decided that it would be settled with a core of German immigrants. The town began to flourish, the court of the Empire of Brazil moving there during the summer months, accompanied by a substantial number of fashionable and wealthy Cariocas, or inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro, who wanted to escape to a more benign climate from the city’s stifling heat.

One of its later residents was the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig. Born in 1881 into the Viennese Jewish bourgeoisie - his father owned a large textile company, and his mother came from from an Austrian-Italian banking family - Zweig soon became famous as an author, and by the 1920s he was the most widely translated writer in the world, his stories and novellas being easily readable, charming and urbane. Cosmopolitan in his tastes, Zweig enjoyed traveling and spent much of his time in other countries, so when the Nazis came to power in Germany and their influence spread to Austria, it was not especially difficult for him to leave Vienna for England, from where he later moved to America at the beginning of World War II.

In the meantime, on one of his many jaunts to foreign places, Zweig had developed an unexpected infatuation with Brazil, which he saw as a place of unlimited potential, and where, in the wake of cultural decay in Europe, civilisation might flourish anew. He wrote a flattering book about the country, and the Brazilian government, normally unenthusiastic about granting refuge to European Jews, gave him a resident’s visa. He made his way to Brazil in 1940, hoping to start a new life, but in marked contrast to his earlier visit, he found on arrival that he was no longer fêted by local politicians and high society, and that his book had been coolly received by the intelligentsia, who considered it to be uninformed and politically credulous.

Zweig rented a modest house on a hillside outside Petrópolis and lived there with his second wife, Lotte Altmann. For a while they were content enough, but Zweig’s pessimism eventually overwhelmed him. Convinced that the world would never again return to civilised ways, he withdrew into depression. Finding it impossible to forget the horrors of the war in Europe, he quickly came to believe that the values he cherished could not survive, even in Brazil, the country in which he had placed such high hopes. Like everything else in later life, his new home deeply disappointed him - ‘In that, I have perhaps never been so Brazilian’, he wrote - and one morning, during the Carnival of 1942, Zweig and his wife took overdoses of barbiturates and died in their bedroom.

The poet Elizabeth Bishop went to Brazil in 1951, almost a decade later. A book of poems, North and South, had earned her a modest reputation in the small world of American poetry, but she was somewhat lonely and restless, and after being awarded a traveling fellowship, she booked a cabin on a freighter, intending to circumnavigate South America. The ship docked in Santos, near São Paulo, and Bishop went ashore, planning to see friends and to stay for a while, but Bishop fell ill, and one of her acquaintances, Lota de Macedo Soares, a Brazilian socialite and architect, helped her recover. Their relationship became intimate, and Bishop soon moved in with Soares. Without having planned it, Bishop, who came from a restrained and relatively puritanical background in New England, found herself living in an unfamiliar tropical country with a new and charismatic companion, and discovered that she felt surprisingly at home with them.

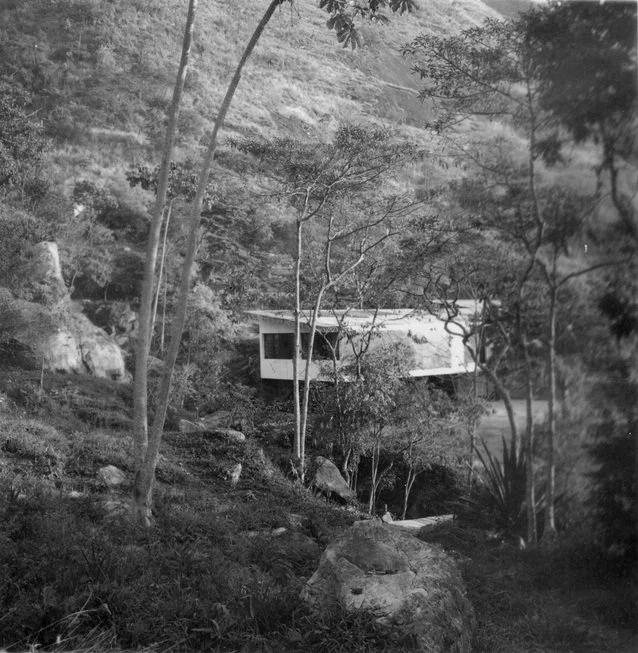

Samambaia, a farm in the hills near Petrópolis, was where Lota Soares built a new glass and steel modernist house. The area, now filled with expensive summer retreats, often in gated estates that are patrolled by uniformed guards and surrounded by razor wire, was then unspoiled and isolated, approached by an unpaved road. Bishop didn’t much like Rio, where Soares kept an apartment, which she considered too busy, noisy, and hot, but she began to enjoy Samambaia and its small community of servants and their families, who lived in and around the impressive new house. She also found herself adjusting to the heat and becoming acceptant of the drawbacks of life in the Brazilian hinterlands. She learnt Portuguese, and although never a fluent speaker, became knowledgeable enough in the language to translate Brazilian literature - including work by Clarice Lispector - into English. Bishop seemed to be adapting to Brazil, and during the fifteen years or so she spent in the country, she wrote many of her best poems.

Bishop wrote a book about Brazil, which - like Zweig’s - was criticised for being lightweight and naive, and in another echo of her predecessor’s life, she began to develop contradictory feelings about her adopted home. The relationship with Lota became complicated, and Bishop bought herself a small house many miles away in Ouro Preto, where she could be more independent. Again like Zweig, she had brought unhappiness to Brazil with her, and the problem was exacerbated by a lifelong dependence on alcohol, with which she would regularly drink herself into insensibility and oblivion. In 1966, looking for change, Bishop left the country to return to America.

Not long afterwards, following a period of hospitalisation caused by a nervous breakdown, Lota Soares visited her friend in New York and died of an overdose of tranquilisers a few days after arriving. Bishop went back to Brazil but was treated with hostility by Soares’ family and friends, who believed that she had some responsibility for Lota’s death. She was bequeathed the apartment in Rio, which she disliked, and Samambaia was left to Soares’ earlier partner. Bishop sold it as quickly as possible and began to cut her ties with the country that had been her home for many years. It would have been difficult for her to do so, as it was in Brazil, and especially in Petrópolis, that Bishop first found a prolonged period of companionship and happiness, and a place where she could escape from the restrictions of America to enjoy personal and creative freedom. She had hitherto always felt isolated and alone. Brazil, however, was also a source of frustration. While grateful for Soares’ affection, as well as her generosity in building a studio for her in the grounds of Samambaia - ‘never in my life had anyone made that kind of gesture toward me, and it just meant everything’, she once wrote - Bishop came to realise that she didn’t belong there.

For further exploration:

Stephan Zweig in Brazil: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20170221-zweig-the-writer-who-dreamed-of-a-world-without-borders

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/08/27/the-escape-artist-3

Elizabeth Bishop in Brazil: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/sep/11/william-boyd-elizabeth-bishop-brazil

https://jls.apsa.us/index.php/jls/article/download/383/401/

Elizabeth Bishop’s studio at Samambaia