Ernst Josephson and C.F. Hill

‘The Holy Sacrament’ by Ernst Josephson

In 1888 the Swedish artist Ernst Josephson began to suffer from mental illness. Finding himself without money while living in France, disturbed and unsettled, he took part in spiritualist séances with a friend; his contact with the ‘other world’ produced a series of trance drawings which Josephson signed with the names of old masters with whom he believed he was in communication, but it may also have exacerbated the emotional problems that had for some time threatened to take hold of him. Persuaded to return to Sweden, he spent a few months in hospital and was later cared for until his death in 1906 by two kindly women. The change in his work after his mental illness was dramatic and profound; paintings made before 1888 were competent and skilled, conveying ease and virtuosity, but later images were utterly different. Many of them anticipated Modernism; ‘The Holy Sacrament’ and ‘Ecstatic Heads’, both made at the end of the decade, and ‘Portrait of Ludwig Josephson’, painted a few years later, are Expressionist in all but name. They were the work of a different personality.

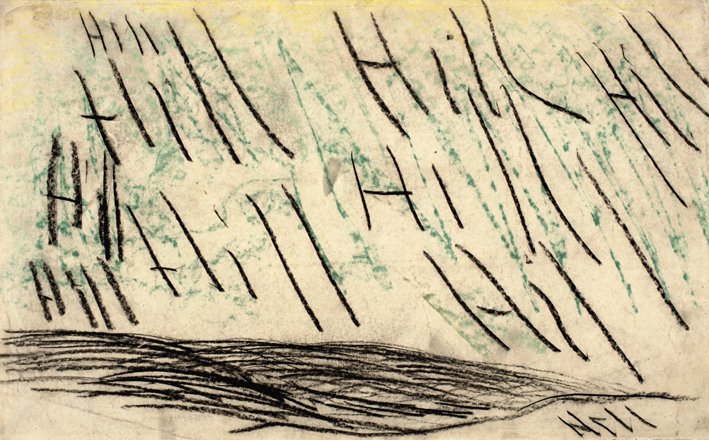

Something similar happened to his compatriot, the painter Carl Frederik Hill. In 1878, at the age of 28, also after a number of years working in France, Hill experienced delusions and paranoia. ’Ambition drives me to over-exert myself and I give myself no peace’, he said, and he went back to his home in Lund, where he was looked after by his mother and sister. Working in solitude at a desk in his late father’s study, he produced several drawings a day, featuring a diverse array of animals, ancient sculptures, people, and landscapes, some of them inspired by the manuscripts and books that surrounded him, others by his inner visions, which were often charged with anxiety and eroticism. His perspective on his own artistic ability remained buoyant; on one of the drawings, ‘Le Coupeur de Gorge’ (‘The Throat-cutter’), he wrote ‘Zeus = C.F. Hill’, and he referred to himself elsewhere as ‘Maximus Pictor’, ‘the greatest of painters’. Unsurprisingly, it was his early paintings that aroused most interest after his death; museums and collectors in Sweden began to purchase them, and for a while Hill was considered to be the country’s ‘Great Landscape Painter’. It was not until 1933 that Hill’s so-called ‘illness drawings’ came to critical attention in the context of an exhibition at the Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, and it is now with these drawings, rather than his accomplished but conventional early landscapes, that he is most often associated.

A year ago the Swedish painter Mamma Andersson and her friend, the Danish artist Tal R, put together an exhibition of their work that was inspired by Hill’s drawings and works on paper. ‘Hill paints beautifully, though I am not so sure that was his intention’, Andersson remarked. ‘He had an incredibly large output during the period he was ill, and I think he drew and painted very much like the way one breathes. You want to get into a state where you no longer think, but just follow and surprise yourself. I sometimes wish that my own process was easier – that it was light as a feather, that I was not so anchored to narrative, that colour and shape could stand on its own. The beauty of Hill’s late drawings is that there is no control whatsoever’.

What would Josephson and Hill have thought about being remembered mainly for work created when they were mentally unwell? Are their late paintings and drawings odd aberrations, intriguing artistic developments, or something entirely different? Since the advent of Modernism, various labels have been attached to artists who nurtured their talents independently, as well as to art that has been considered marginal to the dominant aesthetics of the mainstream ‘art world’. One of them is ‘Outsider Art’, a term that was coined in the 1970s as an equivalent to the earlier French expression ‘Art Brut’, which referred to art made by people who have had little or no artistic training, as well as by children, the mentally ill, and visionaries. Once found firmly outside the boundaries of conventional art discourse and markets, ‘Outsider Art’, now a contested concept, is also a successful marketing category.

Interest in what came to be known as ‘Outsider Art’ was first developed at the end of the first decade of the 20th century by the ‘Blaue Reiter’ group, headed by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, who believed that it had an expressive power that owed much to artistic innocence and lack of sophistication. As Jean Dubuffet, who later conceived and championed the idea of ‘Art Brut’, once explained, ‘Those works created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses – where the worries of competition, acclaim and social promotion do not interfere – are, because of these very facts, more precious than the productions of professionals’. These days, art world attention to ‘Outsider’ practices ebbs and flows in the rapidly changing tides of fashion, and is perhaps most generously described as being part of a broader interrogation of established and conventional cultural values.

The examples of Ernst Josephson and C.F. Hill make it clear that a binary dichotomy between ‘Insider’ and ‘Outsider’ art is essentially meaningless, although it may occasionally be useful. People may make art, or objects that are akin to art, as forms of self-expression or communication, to articulate a need for personal connection, or fear of it; others make things as a way of coming to terms with difficult feelings, such as anger, shame, or grief. Some make art for social purposes, to resist oppression, or to create an internal space in which they can move freely, with a degree of comfort and contentment. A few make things simply for the joy of doing so, for the satisfaction and pleasure of expressing wonder and their love of the world. Technical skill, training, and professional recognition are not unimportant, but they are secondary and often beside the point.

Drawing by C.F.Hill

For further exploration:

Ernst Josephson: https://www.artforum.com/features/the-portland-art-museum-arranges-the-swedish-masters-first-american-retrospective-212001/

C.F.Hill: https://kulturportallund.se/en/hill-carl-fredrik-1849-1911-artist/

Some C.F. Hill images: https://artsandculture.google.com/entity/carl-fredrik-hill/m012rm7?categoryId=artist

Mamma Andersson and Tal R exhibition: https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/526433/tal-r-mamma-anderssonabout-hill/

A useful summary of ‘Outsider Art’ and variant terms: https://rawvision.com/pages/what-is-outsider-art?srsltid=AfmBOorNexJoT2ZS1uEm_X_8lY-V-mdORvM3I98kEQG2f4Ffv91yhpoT

Image on index page: drawing by C.F.Hill

Current listening: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ii63fKLTSuU (with thanks to AE)