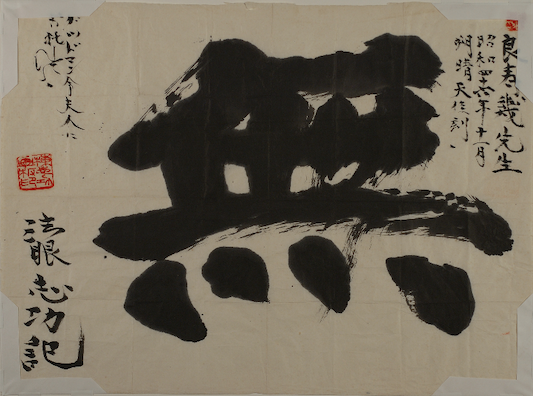

Ozu and ‘Mu’

Original poster for ‘Tokyo Story’

It is said that the 9th century Chinese Chan master Joshu responded to a monk’s question about whether or not a dog has Buddha-nature with the single word ‘Mu!’, and that his answer became one of Zen’s most famous koans. The story may or may not be true, just as the precise meaning of ‘mu’ is impossible to determine. ‘Mu’ is not ‘no’, nor is it exactly ‘nothingness’; it is not even simply negative. Late Buddhism allows for a category of knowledge that transcends the ‘either/or’ dichotomy that is at the heart of classical Western logic, embracing the forbidden possibilities of non-dual ‘neither/nor’ and ‘both’. ‘Mu’ suggests an experience, close to that of Zen ‘satori’, which rises above dualism and the limitations of words and reason.

‘Mu’ is inscribed on the granite tombstone of Yasujiro Ozu, even though Donald Richie, in his classic book on the Japanese film director, says that Ozu is not known to have spoken of the term. It seems to be certain, though, that in 1937, while in the Japanese army, he once asked a local monk in the Chinese city of Nanking for some calligraphy. The monk painted the Chinese version of the character ‘mu’ for him. Later in the book, when Richie wonders if Ozu knew what was really going on in his films, he proposes that Ozu’s thoughts and sensibility may have had so much in common with the concept of ‘mu’ that he didn’t need to think very much about the meaning of his films. He ‘knew’, on another level, what was going on.

The common sense view of Ozu’s mature films is that they are slow and reflective, meticulously constructed, their content almost always focused on the tribulations and challenges that face families in modern Japan. They are carefully realistic and down-to-earth. This is unarguably true, but there is nonetheless an unusual depth and moral simplicity in his work, which is invariably calm, uneventful, and devoid of violence. His films have little interest in dramatic stories about individual characters, preferring to dwell on relationships; social hierarchies are flattened, and everyone is seen to be part of a coherent whole.

Meaning is conveyed more by the films’ aesthetics than by their narrative. Through elimination of everything that is unnecessary, and with his impeccable compositions and restrained use of the camera, Ozu managed to imbue his work with a surprising degree of emotional intensity, which he juxtaposed with moments of peace and spaciousness. Using a trope that has a subliminal effect on the way we ‘read’ the films, he regularly inserted ‘transitional images’ into the narrative, revealing objects, scenes and places that have only an oblique connection with the story, and this has much the same effect as ellipses in writing - they imply pauses, omissions, and unfinished thoughts. Similarly, Ozu often included shots of people looking through windows or gazing into space; he liked to blur the boundary between the subjective and the objective, creating the ‘space between all things’ that is yet another definition of ‘mu’. His films have to be felt, not just watched.

Ozu seems to have been unconcerned that many people found his films too similar, and he was self-effacing about his own talents, once describing himself as a simple ‘tofu-maker’. Immensely loyal to his actors and crew, with whom he liked to work repeatedly, he treated them as his extended family. Some were equally dedicated to him, and his favourite actress, the radiant Setsuko Hara, retired into seclusion after his death in 1963. Although once considered to be too ‘Japanese’ for Western taste, his reputation has continued to grow, and he is now warmly admired by many contemporary directors and critics. His most famous film, Tokyo Story, is widely regarded as one of the finest ever made.

Among Ozu’s most passionate admirers is the film-maker Wim Wenders, who once went to Japan while waiting to begin work on his own film, the beautiful Paris, Texas, and made Tokyo-Ga, a tribute to the master. Wenders has since spoken movingly about Ozu’s ‘soulful gaze’, the integrity of his images, and the ‘holiness’ of every character; Ozu’s films, he says, embody the ‘love of life itself’. This emphasis on the spirituality in Ozu’s work is shared by others, notably Paul Schrader, who has written about it at length in his book Transcendental Style in Film. Some commentators have drawn attention to Ozu’s appreciation of ‘mono no aware’, a Japanese phrase that translates as ‘the pathos of things’ or ‘the awareness of impermanence’; a few have also stressed what they see as the fundamental conservatism, melancholy, and pessimism in his work.

It isn’t clear how Ozu himself might have responded to these assessments of his work and sensibility, and it is possible that he might not have answered, or changed the subject, preferring the ambiguity of ‘mu’. It is indisputable, however, that the detached and affectionate attention with which he beheld life resulted in understated cinematic epiphanies that are close to experiences that many people would call ‘spiritual’. The film director Lindsay Anderson, another admirer, has remarked that Ozu’s liking for low-level ‘tatami’ camera shots reminded him of something that D.T. Suzuki once said, when asked about the nature of ‘satori’, or the moment of Zen awakening. ‘It is just like everyday consciousness’, he replied, ‘but about two inches above the ground’.

For further exploration:

A touching and off-beat documentary on Ozu:

‘Mu’ by Shiko Munagata